Nov. 15, 2012

by Denise Noe

Like any other phenomenon, crime does not exist in a vacuum. It is often a kind of warped, mangled shadow of the era and culture in which it arises. Both the forms that crime takes and the manner in which the general population responds to criminal acts shed light – often an unwanted and unflattering light – on the greater society. One book reviewed here deals with crimes peculiar to the American culture devastated by the Great Depression while another deals with the organized crime culture specific to the Mafia. A book about the infamous Lindbergh baby kidnapping shows how a nation reacted to an especially heinous crime committed against a culture hero by a marginalized immigrant. A final book demonstrates how the wildly differing cultures of Great Britain and Japan were thrown together by both crime and the need to deal with it.

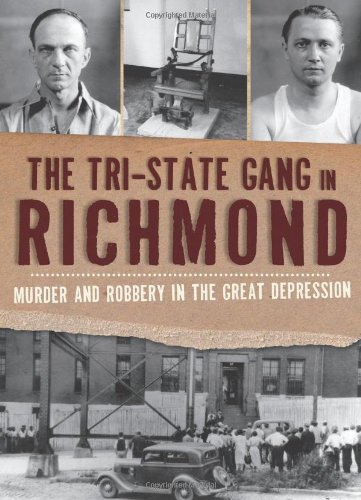

The Tri-State Gang in Richmond: Murder and Robbery in the Great Depression by Selden Richardson (The History Press, 2012, $19.99, 221 pages) is a relatively brief but utterly enthralling book. In the 1930s, with the backdrop of the Great Depression and Prohibition, Richardson brings these desperate times to life by tracking the Tri-State Gang, a handful of criminals out of Philadelphia that went on a crime spree through Baltimore and Richmond. Two of the most prominent members of the Tri-State Gang were Walter Legenza and Robert Mais, both of whom ended their lives in Virginia’s electric chair. While the Tri-State Gang pulled numerous robberies, the crime for which Legenza and Mais were executed was peculiarly misguided. Richmond, Virginia bank employees Ewell Huband and Benjamin Meade found their truck blocked and surrounded. Huband was shot and killed as the gangsters grabbed the bags they were transporting and roared off with them. Later when members of the Tri-State Gang opened the “loot” they found the bags contained only cancelled checks and other paperwork. Numerous photographs help bring both the era and the gang members to life.

The Tri-State Gang in Richmond: Murder and Robbery in the Great Depression by Selden Richardson (The History Press, 2012, $19.99, 221 pages) is a relatively brief but utterly enthralling book. In the 1930s, with the backdrop of the Great Depression and Prohibition, Richardson brings these desperate times to life by tracking the Tri-State Gang, a handful of criminals out of Philadelphia that went on a crime spree through Baltimore and Richmond. Two of the most prominent members of the Tri-State Gang were Walter Legenza and Robert Mais, both of whom ended their lives in Virginia’s electric chair. While the Tri-State Gang pulled numerous robberies, the crime for which Legenza and Mais were executed was peculiarly misguided. Richmond, Virginia bank employees Ewell Huband and Benjamin Meade found their truck blocked and surrounded. Huband was shot and killed as the gangsters grabbed the bags they were transporting and roared off with them. Later when members of the Tri-State Gang opened the “loot” they found the bags contained only cancelled checks and other paperwork. Numerous photographs help bring both the era and the gang members to life.

Images of America: Milwaukee Mafia by Gavin Schmitt (Arcadia Publishing, 2012, $21.99, 127 pages) is primarily a pictorial history of Milwaukee’s Mafia. The photographs re-create a lost era and display a varied roster of diabolical characters. The introduction notes that Milwaukee’s syndicate has been peculiarly neglected by the multitude of books on organized crime: “Milwaukee has never had a single book published about its criminal underworld – not one. . . . Milwaukee has been shortchanged time and again.” Milwaukee Mafia gives the nasty syndicate of the city its devilish due. The book is made up of photographs from the early days of the 20th century to the wind-up of the Milwaukee Mafia when its last known boss, Frank Balistrieri, died in 1993. Interestingly, the Milwaukee Mafia is believed to have died when this mobster shucked off his mortal coil (of natural causes). A reader is apt to linger over many of these extraordinary photographs. Mug shots show a bewildering array of expressions: blasé and detached, menacing and hateful, even coy and quasi-flirtatious. Gangsters often appear fascinatingly normal in wedding pictures and family photographs as well as candid shots of them chatting. The book includes pictures of taverns and attractive restaurants that served as venues for heinous crimes as well as gathering places for mobsters. Some of the photographs are intriguingly eccentric. For example, we see two photographs of dwarf Pasquale Scalici, also appropriately called Frank Little, a former circus clown who was also a bookie. One picture shows him outdoors with a group of people. The other shows him beside baseball legend Babe Ruth. Another eccentric photograph shows the patented drawing of a “device for pouring alcohol from bottles which is still used today.” This invention has the distinction of being created by a mobster who was imprisoned for murder. Images of America: Milwaukee Mafia has the distinction of being the first book to open a window into that city’s organized crime scene. It will undoubtedly enthrall readers with its clear portrayal of that lost underworld.

Images of America: Milwaukee Mafia by Gavin Schmitt (Arcadia Publishing, 2012, $21.99, 127 pages) is primarily a pictorial history of Milwaukee’s Mafia. The photographs re-create a lost era and display a varied roster of diabolical characters. The introduction notes that Milwaukee’s syndicate has been peculiarly neglected by the multitude of books on organized crime: “Milwaukee has never had a single book published about its criminal underworld – not one. . . . Milwaukee has been shortchanged time and again.” Milwaukee Mafia gives the nasty syndicate of the city its devilish due. The book is made up of photographs from the early days of the 20th century to the wind-up of the Milwaukee Mafia when its last known boss, Frank Balistrieri, died in 1993. Interestingly, the Milwaukee Mafia is believed to have died when this mobster shucked off his mortal coil (of natural causes). A reader is apt to linger over many of these extraordinary photographs. Mug shots show a bewildering array of expressions: blasé and detached, menacing and hateful, even coy and quasi-flirtatious. Gangsters often appear fascinatingly normal in wedding pictures and family photographs as well as candid shots of them chatting. The book includes pictures of taverns and attractive restaurants that served as venues for heinous crimes as well as gathering places for mobsters. Some of the photographs are intriguingly eccentric. For example, we see two photographs of dwarf Pasquale Scalici, also appropriately called Frank Little, a former circus clown who was also a bookie. One picture shows him outdoors with a group of people. The other shows him beside baseball legend Babe Ruth. Another eccentric photograph shows the patented drawing of a “device for pouring alcohol from bottles which is still used today.” This invention has the distinction of being created by a mobster who was imprisoned for murder. Images of America: Milwaukee Mafia has the distinction of being the first book to open a window into that city’s organized crime scene. It will undoubtedly enthrall readers with its clear portrayal of that lost underworld.

New Jersey’s Lindbergh Kidnapping and Trial by Mark W. Falzini and James Davidson (Arcadia Publishing, 2012, $21.99, 127 pages) is a pictorial history of the sensational Lindbergh baby kidnapping case, the discovery just over two months later of the baby’s corpse in a shallow grave less than five miles from the Lindbergh’s estate in Hopewell, New Jersey, and the investigation that led to the arrest, trial, conviction and execution of Richard Hauptmann in 1936. The book features more than 150 photographs that have been out of circulation for more than 80 years. The authors present a straightforward, understated commentary that succinctly presents this terribly controversial case, including Hauptmann’s claims of innocence, but it avoids delving into the many controversies that still hound the “crime of the century.”

New Jersey’s Lindbergh Kidnapping and Trial by Mark W. Falzini and James Davidson (Arcadia Publishing, 2012, $21.99, 127 pages) is a pictorial history of the sensational Lindbergh baby kidnapping case, the discovery just over two months later of the baby’s corpse in a shallow grave less than five miles from the Lindbergh’s estate in Hopewell, New Jersey, and the investigation that led to the arrest, trial, conviction and execution of Richard Hauptmann in 1936. The book features more than 150 photographs that have been out of circulation for more than 80 years. The authors present a straightforward, understated commentary that succinctly presents this terribly controversial case, including Hauptmann’s claims of innocence, but it avoids delving into the many controversies that still hound the “crime of the century.”

People Who Eat Darkness by Richard Lloyd Parry (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012, $16.00, 454 pages) is an incredibly well-told account of the disappearance and murder of 21-year-old Lucie Blackman, a tall, blond Londoner who moved to Tokyo with her best friend in 2000 to work as “hostesses” in one of the city’s notorious entertainment districts. Lucie’s abduction occurred 59 days after her arrival and, thanks to her father’s persistence, became a major news story in both Japan and Great Britain that engaged the highest levels of both Japan and Great Britain’s governments. Written by Richard Lloyd Parry, the Asian editor and bureau chief of The Times of London, the book presents a rare look inside the Japanese justice system that is so radically different from the United States and the UK. For this tutorial alone, the book should be read. Parry also explores in great depth the family dynamics that are set off within Lucie’s family as the seven month search for her corpse plays out and the trial of her accused killer spans a six-year period.

People Who Eat Darkness by Richard Lloyd Parry (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012, $16.00, 454 pages) is an incredibly well-told account of the disappearance and murder of 21-year-old Lucie Blackman, a tall, blond Londoner who moved to Tokyo with her best friend in 2000 to work as “hostesses” in one of the city’s notorious entertainment districts. Lucie’s abduction occurred 59 days after her arrival and, thanks to her father’s persistence, became a major news story in both Japan and Great Britain that engaged the highest levels of both Japan and Great Britain’s governments. Written by Richard Lloyd Parry, the Asian editor and bureau chief of The Times of London, the book presents a rare look inside the Japanese justice system that is so radically different from the United States and the UK. For this tutorial alone, the book should be read. Parry also explores in great depth the family dynamics that are set off within Lucie’s family as the seven month search for her corpse plays out and the trial of her accused killer spans a six-year period.